During the Renaissance, an epoch in (primarily) European history, which lasted from the 14th to the 17th century, not only the mathematics but also the culture, philosophy, and art of classical ancient Greek and Roman heritage was rediscovered. Great technical progress was made in mechanics, in particular, in the construction of machines, but also in the military, the astronomy, the construction of clocks, and in nautical science. The greatest achievements of the epoch were Tycho Brahe's (1546 - 1601) and Johannes Kepler's (1571 - 1630) discoveries in astronomy. They have shown that it was possible to describe the laws of motions of planets by mathematical formulas. The possibility of being able to describe heavenly movements by earthly mathematics inspired philosophers and scientists to come and nurtured the faith in the omnipotence of the human mind.

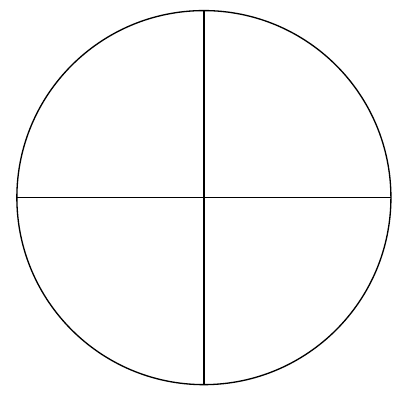

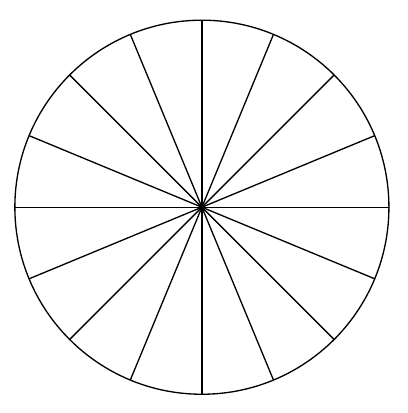

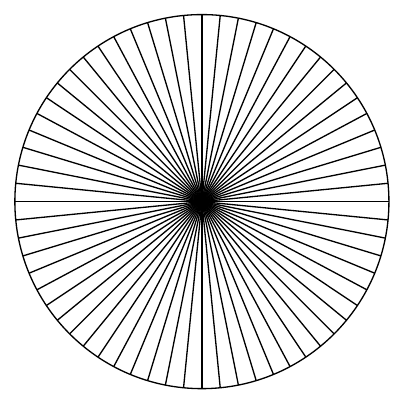

But Kepler also turned towards more banal themes like the calculations of volumes of wine barrels. In his "Nova stereometria doliorum vinariorum" published in 1615, he invented methods to calculate the area of the circle as a sum of vanishingly small triangles and the volume of a ball as the sum of volumes of vanishingly small cones. The following figure visualizes his idea for calculating the area of the circle:

Although new and revolutionary, Kepler's methods were lacking the rigor of mathematics developed by ancient greeks like Euclid and Aristotle.

Galileo Galilei (1564 - 1642) developed in his "Discorsi" (1638) the laws governing the movement of bodies. In particular, he described the velocity as the change of position in time and the acceleration as the change of velocity in time. In this sense, Galilei was one of the first mathematicians who handled with the concept of a function. Moreover, Galilei described his functions (without calling them so) as "continues" dependencies, but he neither defined exactly, what such a dependency (a function) should be, nor he explained in a systematical and rigorous way what "continues" meant. The following observation of Galilei is remarkable: He argued that it would not make sense to say that there are "less" or "more" square numbers than natural numbers. In particular, inequations known from finite magnitudes were not necessarily valid for infinite magnitudes. This remarkable observation made by Galilei was confirmed only two centuries later by Georg Cantor (1845 - 1918). In 1613, Galilei confirmed the results of Copernicus that not the Sun orbits the Earth but vice versa. But he was obliged to revoke this confirmation under the threat of torture by the Catholic Church - and he revoked it.

Francesco Cavalieri (1598 - 1630) was a pupil of Galilei. He invented a method for calculation of areas and volumes, known as Cavalieri's principle, which stated that * (2-dimensional case): two areas are equal if lines cutting both areas at the same hights have the same lengths, * (3-dimensional case): two bodies have the same volumes if flat cuts of both bodies done at the same hights have the same areas.

With this principle, it was possible for Cavalieri to do calculations similar to the modern analytical integration of polynomials. However, another pupil of Galileo, Evangelista Torricelli (1608 - 1647), found argument flaws in Cavalieri's principle, because he argued that using such a principle, it was possible to add up lines (which had no area at all) to an area cuts, which had no volume at all to a volume. To meet this objection, Cavalieri changed his principle by replacing lines by threads, i.e. he replaced his lines by "very narrow" rectangles and he replaced his "cuts" by "very narrow" plates.

These works developed by Kepler, Galilei, Cavalieri, and Torricelli and other methods and developments paved the way for the invention of infinitesimal methods by Newton and von Leibniz in the 17th century.

Chapters: 1