(related to Problem: The Four Frogs)

The fewest possible moves, counting every move separately, are sixteen. But the puzzle may be solved in seven plays, as follows if any number of successive moves by one frog count as a single play. All the moves contained within a bracket are a single play; the numbers refer to the toadstools: $(1—5), (3—7, 7—1), (8—4, 4—3, 3—7), (6—2, 2—8, 8—4, 4—3), (5—6, 6—2, 2—8), (1—5, 5—6), (7—1).$

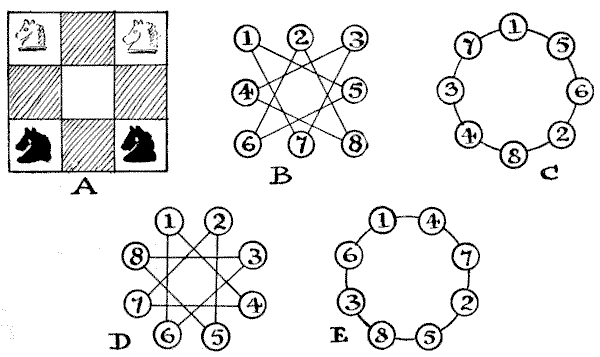

This is the familiar old puzzle by Guarini, propounded in $1512,$ and I give it here in order to explain my "buttons and string" method of solving this class of moving-counter problem.

Diagram $A$ shows the old way of presenting Guarini's puzzle, the point is to make the white knights change places with the black ones. In "The Four Frogs" presentation of the idea the possible directions of the moves are indicated by lines, to obviate the necessity of the reader's understanding the nature of the knight's move in chess. But it will at once be seen that the two problems are identical. The central square can, of course, be ignored, since no knight can ever enter it. Now, look at the toadstools as buttons and the connecting lines as strings, as in Diagram $B.$ Then by disentangling these strings we can clearly present the diagram in the form shown in Diagram $C,$ where the relationship between the buttons is precisely the same as in B. Any solution on $C$ will be applicable to $B,$ and to $A.$ Place your white knights on $1$ and $3$ and your black knights on $6$ and $8$ in the $C$ diagram, and the simplicity of the solution will be very evident. You have simply to move the knights around the circle in one direction or the other. Play over the moves given above, and you will find that every little difficulty has disappeared.

In Diagram $D$ I give another familiar puzzle that first appeared in a book published in Brussels in 1789, Les Petites Aventures de Jerome Sharp. Place seven counters on seven of the eight points in the following manner. You must always touch a point that is vacant with a counter, and then move it along a straight line leading from that point to the next vacant point (in either direction), where you deposit the counter. You proceed in the same way until all the counters are placed. Remember you always touch a vacant place and slide the counter from it to the next place, which must be also vacant. Now, by the "buttons and string" method of simplification we can transform the diagram into $E.$ Then the solution becomes obvious. "Always move to the point that you last moved from." This is not, of course, the only way of placing the counters, but it is the simplest solution to carry in the mind.

There are several puzzles in this book that the reader will find lend themselves readily to this method.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this edition or online at http://www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.