(related to Problem: The Icosahedron Puzzle)

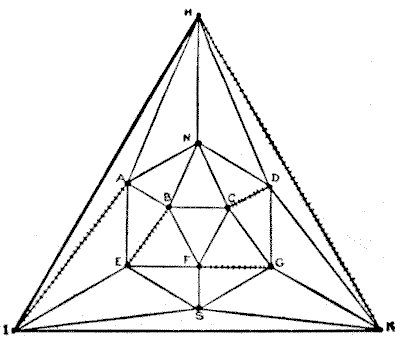

There are thirty edges, of which eighteen were visible in the original illustration, represented in the following diagram by the hexagon $NAESGD.$ By this projection of the solid, we get an imaginary view of the remaining twelve edges and are able to see at once their direction and the twelve points at which all the edges meet. The difference in the length of the lines is of no importance; all we want is to present their direction in a graphic manner. But in case the novice should be puzzled at only finding nineteen triangles instead of the required twenty, I will point out that the apparently missing triangle is the outline $HIK.$

In this case, there are twelve odd nodes; therefore six distinct and disconnected routes will be needful if we are not to go over any lines twice. Let us, therefore, find the greatest distance that we may so travel in one route.

It will be noticed that I have struck out with little cross strokes five lines or edges in the diagram. These five lines may be struck out anywhere so long as they do not join one another, and so long as one of them does not connect with $N,$ the North Pole, from which we are to start. It will be seen that the result of striking out these five lines is that all the nodes are now even except $N$ and $S.$ Consequently if we begin at $N$ and stop at $S$ we may go over all the lines, except the five crossed out, without traversing any line twice. There are many ways of doing this. Here is one route: $N$ to $H,$ $I,$ $K,$ $S,$ $I,$ $E,$ $S,$ $G,$ $K,$ $D,$ $H,$ $A,$ $N,$ $B,$ $A,$ $E,$ $F,$ $B,$ $C,$ $G,$ $D,$ $N,$ $C,$ $F,$ $S.$ By thus making five of the routes as short as is possible — simply from one node to the next — we are able to get the greatest possible length for our sixth line. A greater distance in one route, without going over the same ground twice, it is not possible to get.

It is now readily seen that those five erased lines must be gone over twice, and they may be "picked up," so to speak, at any points of our route. Thus, whenever the traveler happens to be at I he can run up to $A$ and back before proceeding on his route, or he may wait until he is at $A$ and then run down to $I$ and back to $A.$ And so with the other lines that have to be traced twice. It is, therefore, clear that he can go over $25$ of the lines once only ($25 \times 10,000$ miles = $250,000$ miles) and $5$ of the lines twice ($5 \times 20,000$ miles = $100,000$ miles), the total, $350,000$ miles, being the length of his travels and the shortest distance that is possible in visiting the whole body.

It will be noticed that I have made him end his travels at $S,$ the South Pole, but this is not imperative. I might have made him finish at any of the other nodes, except the one from which he started. Suppose it had been required to bring him home again to $N$ at the end of his travels. Then instead of suppressing the line $AI$ we might leave that open and close $IS.$ This would enable him to complete his $350,000$ miles tour at $A,$ and another $10,000$ miles would take him to his own fireside. There are a great many different routes, but as the lengths of the edges are all alike, one course is as good as another. To make the complete $350,000$ miles tour from $N$ to $S$ absolutely clear to everybody, I will give it entire: $N$ to $H,$ $I, A,$ $I, K,$ $H, K,$ $S, I,$ $E, S,$ $G, F,$ $G, K,$ $D, C,$ $D, H,$ $A, N,$ $B, E,$ $B, A,$ $E, F,$ $B, C, G,$ $D, N,$ $C, F,$ $S$ — that is, thirty-five lines of $10,000$ miles each.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this edition or online at http://www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.