"By magic numbers."CONGREVE, The Mourning Bride.

This is a very ancient branch of mathematical puzzledom, and it has an immense, though scattered, a literature of its own. In their simple form of consecutive whole numbers arranged in a square so that every column, every row, and each of the two long diagonals shall add up alike, these magic squares offer three main lines of investigation: Construction, Enumeration, and Classification. Of recent years many ingenious methods have been devised for the construction of magics, and the law of their formation is so well understood that all the ancient mystery has evaporated and there is no longer any difficulty in making squares of any dimensions. Almost the last word has been said on this subject. The question of the enumeration of all the possible squares of a given order stands just where it did over two hundred years ago. Everybody knows that there is only one solution for the third order, three cells by three; and de Bessy published in 1693 diagrams of all the arrangements of the fourth order—880 in number—and his results have been verified over and over again. I may here refer to the general solution for this order, for numbers not necessarily consecutive, by E. Bergholt in Nature, May 26, 1910, as it is of the greatest importance to students of this subject. The enumeration of the examples of any higher order is a completely unsolved problem.

As to classification, it is largely a matter of individual taste—perhaps an esthetic question, for there is beauty in the law and order of numbers. A man once said that he divided the human race into two great classes: those who take snuff and those who do not. I am not sure that some of our classifications of magic squares are not almost as valueless. However, lovers of these things seem somewhat agreed that Nasik magic squares (so named by Mr. Frost, a student of them, after the town in India where he lived, and also called Diabolique and Pandiagonal) and Associated magic squares are of special interest, so I will just explain what these are for the benefit of the novice.

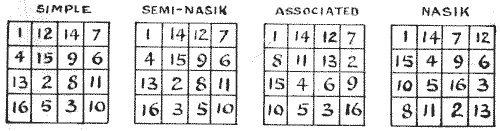

I published in The Queen for January 15, 1910, an article that would enable the reader to write out, if he so desired, all the $880$ magics of the fourth order, and the following is the complete classification that I gave. The first example is that of a Simple square that fulfills the simple conditions and no more. The second example is a Semi-Nasik, which has the additional property that the opposite short diagonals of two cells each together sum to $34.$ Thus, $14 + 4 + 11 + 5 = 34$ and $12 + 6 + 13 + 3 = 34.$ The third example is not only Semi-Nasik but also Associated, because in it every number, if added to the number that is equidistant, in a straight line, from the center gives $17.$ Thus, $1 + 16,$ $2 + 15,$ $3 + 14,$ etc. The fourth example, considered the most "perfect" of all, is a Nasik. Here all the broken diagonals sum to $34.$ Thus, for example, $15 + 14 + 2 + 3,$ and $10 + 4 + 7 + 13,$ and $15 + 5 + 2 + 12.$ As a consequence, its properties are such that if you repeat the square in all directions you may mark off a square, $4 \times 4,$ wherever you please, and it will be magic.

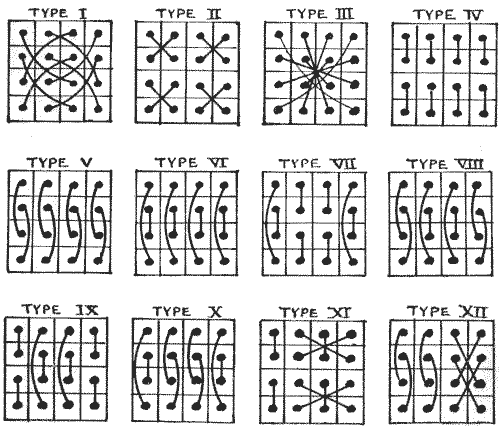

The following table not only gives a complete enumeration under the four forms described but also a classification under the twelve graphic types indicated in the diagrams. The dots at the end of each line represent the relative positions of those complementary pairs, $1 + 16,$ $2 + 15,$ etc., which sum to $17.$ For example, it will be seen that the first and second magic squares given are of Type VI., that the third square is of Type III., and that the fourth is of Type I. Edouard Lucas indicated these types, but he dropped exactly half of them and did not attempt the classification.

| NASIK | (Type I.) | 48 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEMI-NASIK | (Type II., Transpositions of Nasik) | 48 | ||

| " | (Type III., Associated) | 48 | ||

| " | (Type IV.) | 96 | ||

| " | (Type V.) | 96 | 192 | |

| " | (Type VI.) | 96 | 384 | |

| SIMPLE | (Type VI.) | 208 | ||

| " | (Type VII.) | 56 | ||

| " | (Type VIII.) | 56 | ||

| " | (Type IX.) | 56 | ||

| " | (Type X.) | 56 | 224 | |

| " | (Type XI.) | 8 | ||

| " | (Type XII.) | 8 | 16 | 448 |

| Total | 880 |

It is hardly necessary to say that every one of these squares will produce seven others by mere reversals and reflections, which we do not count as different. So that there are $7,040$ squares of this order, 880 of which are fundamentally different.

An infinite variety of puzzles may be made introducing new conditions into the magic square. In The Canterbury Puzzles I have given examples of such squares with coins, with postage stamps, with cutting-out conditions, and other tricks. I will now give a few variants involving further novel conditions.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this edition or online at http://www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.