"I cannot do't without counters." Winter's Tale, iv. 3.

Puzzles of this class, except so far as they occur in connection with actual games, such as chess, seem to be a comparatively modern introduction. Mathematicians in recent times, notably Vandermonde and Reiss, have devoted some attention to them, but they do not appear to have been considered by the old writers. So far as games with counters are concerned, perhaps the most ancient and widely known in old times is "Nine Men's Morris" (known also, as I shall show, under a great many other names), unless the simpler game, distinctly mentioned in the works of Ovid (No. 110, "Ovid's Game," in The Canterbury Puzzles), from which "Noughts and Crosses" seems to be derived, is still more ancient.

In France the game is called Marelle, in Poland Siegen Wulf Myll (She-goat Wolf Mill, or Fight), in Germany and Austria it is called Muhle (the Mill), in Iceland it goes by the name of Mylla, while the Bogas (or native bargees) of South America are said to play it, and on the Amazon it is called Trique, and held to be of Indian origin. In our own country, it has different names in different districts, such as Meg Merrylegs, Peg Meryll, Nine Peg o'Merryal, Nine-Pin Miracle, Merry Peg, and Merry Hole. Shakespeare refers to it in "Midsummer Night's Dream" (Act ii., scene 1):—

"The nine-men's morris is filled up with mud; And the quaint mazes in the wanton green, For lack of tread, are undistinguishable."

It was played by the shepherds with stones in holes cut in the turf. John Clare, the peasant poet of Northamptonshire, in "The Shepherd Boy" (1835) says:—"Oft we track his haunts .... By nine-peg-morris nicked upon the green." It is also mentioned by Drayton in his "Polyolbion."

It was found on an old Roman tile discovered during the excavations at Silchester and cut upon the steps of the Acropolis at Athens. When visiting the Christiania Museum a few years ago I was shown the great Viking ship that was discovered at Gokstad in 1880. On the oak planks forming the deck of the vessel were found boles and lines marking out the game, the holes being made to receive pegs. While inspecting the ancient oak furniture in the Rijks Museum at Amsterdam I became interested in an old catechumen's settle and was surprised to find the game diagram cut in the center of the seat—quite conveniently for surreptitious play. It has been discovered cut in the choir stalls of several of our English cathedrals. In the early eighties, it was found scratched upon a stone built into a wall (probably about the date 1200), during the restoration of Hargrave church in Northamptonshire. This stone is now in the Northampton Museum. A similar stone has since been found at Sempringham, Lincolnshire. It is to be seen on an ancient tombstone in the Isle of Man and painted on old Dutch tiles. And in 1901 a stone was dug out of a gravel pit near Oswestry bearing an undoubted diagram of the game.

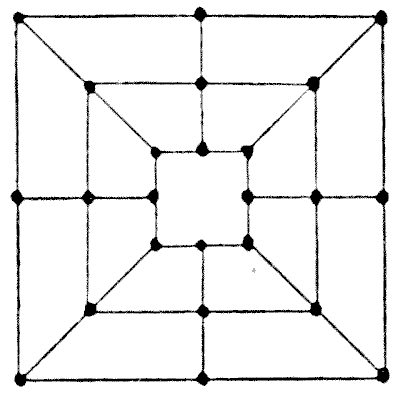

The game has been played with different rules at different periods and places. I give a copy of the board. Sometimes the diagonal lines are omitted, but this evidently was not intended to affect the play: it simply meant that the angles alone were thought sufficient to indicate the points. This is how Strutt, in Sports and Pastimes, describes the game, and it agrees with the way I played it as a boy:—"Two persons, having each of the nine pieces, or men, lay them down alternately, one by one, upon the spots; and the business of either party is to prevent his antagonist from placing three of his pieces so as to form a row of three, without the intervention of an opponent piece. If a row be formed, he that made it is at liberty to take up one of his competitor's pieces from any part he thinks most of his advantage; excepting he has made a row, which must not be touched if he has another piece on the board that is not a component part of that row. When all the pieces are laid down, they are played backward and forwards, in any direction that the lines run, but only can move from one spot to another (next to it) at one time. He that takes off all his antagonist's pieces is the conqueror."

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this edition or online at http://www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.